Leonid Alexandrovich Ouspensky

1902-1987

A Short Biography by Lydia Alexandrovna Ouspensky

Leonid Alexandrovich Ouspensky was born in 1902, on his father’s estate in the village of Golaia Snova (now Golosnovka), in the north of the Voronezh region in Russia. His father was a not very wealthy member of the local gentry, holding a small estate. His mother (nee Kutuzova) was a country woman. Leonid had two younger sisters, Alexandra and Anna.

As the nearest school to the family estate was in Zadonsk, 70 kilometers away, Leonid Alexandrovich Ouspensky studied in the Zadonski Gymnasium (Middle School), returning home to his father’s estate for vacations. From 1914 on, when many of the field workers were mobilized in order to serve in the Russian army during the First World War, he went out with his father each day to do field work, which he liked very much. Until late old age he was able to scythe hay very well.

His studies proceeded normally until 1917, when the serious disorders sweeping Russia reached his Gymnasium. All kinds of organizations appeared, and a student committee was formed. Young Ouspensky was the chief instigator behind many disorders and changes in the student body. At that time he was a convinced atheist, and he traveled around the villages of the region preaching atheism. He entered homes and threw icons out of the windows. Looking older than his 15 years, he had great authority among his fellow pupils, to the extent that, having gathered together a group of five of his classmates, all fifteen or sixteen years old, he convinced them to leave school with him to enlist in the Red Army. Because of their age, the boys were refused and sent back to school. Nevertheless, a few months later, while staying at his father’s estate, Ouspensky again tried to enlist in the army. This time he was accepted and, in 1918, he went to war.

He began his military career with a severe attack of typhus, which continued to plague him while traveling on a military train. He was moved from his cargo seat to a hospital car, where he eventually recovered. The train slowly went from city to city, trying to find hospital space for the sick. But all the hospitals were overcrowded, and there was neither medicine nor food for the sick. Soon after the crisis passed, still very weak, Ouspensky was taken off the train at Ekaterinodar. He staggered up and down the streets, knocking on every door, trying to get under someone’s roof. But all the doors were shut by horrified householders – here was a man with typhus! A cobbler finally took him in, fed him, and gave him a place to sleep. Once recovered, Ouspensky rejoined the war in the Red Army.

He was enrolled in the Zhloba Cavalry Division, which was busy disarming the mountain villagers in the Caucases. The fate of this Division is well-known. From 8,000 men in 1917, only a few dozen remained alive in June, 1920. Ouspensky’s survival occurred in the following way. The division was usually highly mobile, but at one point it had to stay in one village for several days. When it moved out of the village one morning, several fighters — Ouspensky among them — were forgotten and left behind, sound asleep. When they awoke, they tried to catch up with their comrades. But as they caught up with them, they saw their Division trapped in a ravine, where the White Artillery was firing directly down on them from superior positions on three sides. There was chaos in the ravine, with soldiers, horses and weapons all tangled together. Out of this chaos, a group led by a flag-bearer scrambled uphill to join Ouspensky’s little group. They were looking for a way to go around the White Army which had encircled them, but they ran into a White Infantry Detachment which, seeing their red flag, sprayed them with automatic fire. Ouspensky’s horse was killed instantly, and he himself was sent flying over its head. He found himself lying on the grass at some distance, unscathed and entirely alone.

He was quickly captured and brought to military trial, where he was condemned on the spot to death by firing squad. He stood at the edge of an open grave into which he was to fall, while the soldiers raised their rifles, waiting for the lieutenant’s command to fire. The fact that he survived seemed to him later the merest chance: it happened that at this very moment a colonel rode by and, instead of giving the command to fire, he commanded the firing squad to stop. He ordered that Ouspensky should be put to work in the White Army. The rifles were lowered; the execution stopped, and Ouspensky was enrolled in the artillery of Kornilov, one of the White Generals. He was, however, under constant surveillance and, in the event of any suspicious words or actions, there was the threat of execution without warning. This was no empty threat. Other Red prisoners were to disappear after being goaded into saying the wrong thing by deliberately planted provocateurs. Under this severe regimen, Ouspensky learned the value of silence, and would remain moderate in speech for the rest of his life.

In later years, Leonid was asked by his wife, Lydia Alexandrevna, whether he had been afraid. He said that he had been too shocked by what he had gone through to feel anything at all. He looked down at his feet and, seeing grass, thought that never had he seen such extraordinary beauty.

This experience was not the worst that he lived through during the civil war. He later remembered seeing an unarmed captive executed by sabers. As his executioners struck him, the man, desperate, shouted, “Brothers, brothers — what are you doing?” Afterwards, moaning and sounding the death rattle, he fell and writhed convulsively on the ground until he was hacked to bits like a piece of meat. This experience left a deep impression on Ouspensky, who remained unconditionally intolerant of the killing of any living creatures for the rest of his life.

Leonid Ouspensky retreated with the White Army to Sevastopol and was evacuated. He had thought of remaining in the city, hiding and waiting for the arrival of the Red Army. But there was no place to hide. Also, the thought of seeing Constantinople attracted him, and like all of us, he thought the civil war would not last long. But he didn’t manage to see Constantinople. He was unloaded immediately at Gallipoli.

After suffering and starving there with a group of friends, Ouspensky found himself in Bulgaria. He worked hard there at a salt plant, then in a vineyard, and later as a quarry-worker. He was often starving, to the extent that he became temporarily blind from malnutrition.

Afterwards, Ouspensky went to a coal mine at Pernik and worked there until 1926 under a miner’s difficult conditions, in constant danger. He was wounded twice, but he no longer starved. At that time recruiters came from France offering work contracts for jobs which the French did not want to do, for which they used foreigners. At that time it fell to Italians, Poles and Russians to do this kind of work. Ouspensky signed a one-year contract with the Schneider Firm at Creusot, and that is how he came to France. He was assigned a job at a foundry. After having worked for a few months, he stepped into some molten metal and, severely burned, he lay in hospital for several weeks. The conditions in which people found themselves under these contracts were such that, after coming out of hospital, Ouspensky paid the millionaire Schneider compensation for failing to fulfill his contract. He left for Paris to work in a factory producing bicycle parts.

In 1929, on the initiative of Tatiana Lvovna Sukhotine-Tolstoi, an Academy of Arts was opened in Paris, at which many well-known artists taught. Ouspensky enrolled. Until that point his love for painting had found its sole expression in his meticulous copying of post cards with flowers. After entering the Academy he began working at the bicycle factory on a piece-work basis. Managing to fulfill his norms before noon, he dedicated his remaining hours to painting. Soon he left the plant altogether, which resulted in a difficult existence with meager earnings from sporadic manual labour, such as unloading cargo carriages at night.

In its initial form the Academy, after only a short time, collapsed because of financial disasters. But a group of students continued working, mainly under the leadership of N.D. Millioti. In the Academy Ouspensky met two people who were to play an important role in his life — his first wife, also an artist, and Georgii Ivanovich Krug, the future Monk Gregory. While the marriage proved short-lived, the friendship with Georgii Ivanovich lasted for the rest of his life.

The whole company spent summer vacations at the summer villa of K. A. Somov in Normandy. Out of these summer sessions came creative, talented drawings and portraits which the aspiring painters made of each other.

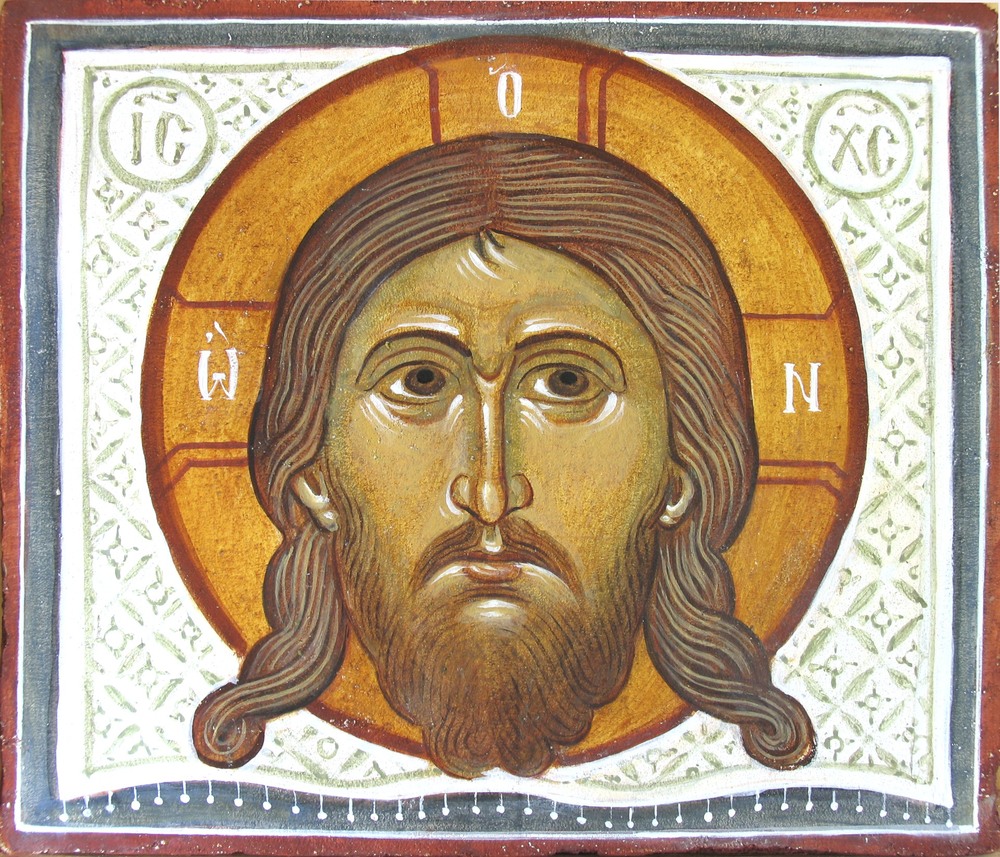

At that time all the students, including Ouspensky, began to earn money by painting on orders from the large clothing stores of Paris, designing and painting on textile for reproduction on scarves. It was not long before he painted his first icon, but in a rather odd way: as a result of a conversation about icons and icon painting, in which he expressed the opinion that it was not a very difficult thing to do, a friend had challenged him by saying that he could not paint an icon successfully. He took up the challenge, but immediately after he finished this work he destroyed it, realizing that he had done something inappropriate. Gradually, through a growing, serious interest in the icon, he came to a genuine faith and returned to the Church. In time, together with Georgii Ivanovich Krug, he decided to leave secular painting altogether and to devote himself exclusively to icon painting. Georgii Ivanovich Krug already knew a little about the technique of icon painting, which he had learned when he lived in Estonia. But Ouspensky began by taking several lessons from the Russian icon painter Fyodorov. Later he had to work on his own because he lacked funds to pay for these lessons. At that time the antique shops in Paris still had many good icons. Ouspensky would study them for hours, scrutinizing them in a professional way. Later he would say that these ancient icons had been his real teachers.

In the late 1930’s he followed Georgii Ivanovich Krug and joined the association of Orthodox theologians, intellectuals and artists in Paris known as the “Stavropegial Brotherhood of Saint Photios .” There he became close to the theologian, Vladimir Nikolaevich Lossky, and to the brothers, Maxim and Evgraf Kovalevsky.

Each member of the Brotherhood worked in his own field. Vsevolod Palashkovski was a liturgist; Maxim Kovalevsky was a great and talented master of Church singing and a choir director; his brother, the future Archpriest Evgraf Kovalevsky, was a brilliant canonist; Vladimir Lossky was already a famous theologian (by the time the war had begun in 1939); Georgii Ivanovich Krug and Leonid Alexandrovich Ouspensky were icon painters.

The Brotherhood had other members. It met once a week at the homes of the various members. At these meetings each member discussed his work in progress. The overall work of the Brotherhood was enriched by contacts with the Moscow Patriarchate. At that time the Brotherhood of Saint Photios played an important role in the life of the Church in France. It proved decisive in the formation of Patriarchal parishes. These were to become the Exarchate of the Moscow Patriarchate when the schism of 1931 divided the Russian communities in Western Europe. In 1936 the reception into the Orthodox Church of the first large group of French people took place, largely thanks to the work and witness of members of the Brotherhood. When the Russian community became divided over the question of sophiology, members of the Brotherhood again played a leading role in clarifying the issue and defending the Church’s doctrinal integrity. And that role consisted, essentially, in the recovery of the Patristic spirit of the Church, and the re-assertion of the traditional place of the Eucharist and the Liturgy in the life of the community. This work was tragically interrupted by the Second World War and the German occupation of Paris.

At the time of the Occupation, Ouspensky was mobilized for work in Germany in military plants. Refusal was equivalent to desertion. Therefore he had to go underground and hide since the German police (and, less zealously, the French police) were looking for him. His underground existence had one benefit – no longer able to paint for secular patrons, he could dedicate himself entirely to icon painting and wood carving and, afterwards, to icon restoration. In 1942 Ouspensky married Lydia Alexandrevna Miagkov. In August, 1944, Paris was liberated under conditions of great suffering and upheaval. However, order was eventually restored throughout the city and life began to return to normal.

The Brotherhood, which, when the Occupation began, was organizing theological conferences with different confessions for the sake of informal, private contacts, was now able to organize a French theological institute — L’Institut Saint Denis — dedicated to Saint Dionysios the Areopagite. This was a different institution from the other Russian Orthodox theological institute in Paris — L’Institut Saint Serge. The rector of L’Institut Saint Denis was the renowned theologian, Vladimir Lossky. A course of icon painting was established at the Institute and entrusted to Leonid Ouspensky, who taught it for 40 years thereafter. The schism in the Brotherhood — fomented by a former member, Archpriest Kovalevsky — led to the departure of a group loyal to him and, ultimately, created a schism within the Russian Church in France. This history has already been studied and does not need to be repeated here. But as a result of these events the icon painting course came under the immediate authority of the Exarchate of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Because it was often misunderstood, icon painting needed to be explained, and so in 1948, Leonid Ouspensky published L’Icone, Vision du Monde Spirituel, a small brochure in French explaining some aspects of the icon. When this work was read by the renowned Greek icon painter, Photios Kontoglou, he supervised a Greek translation of the brochure, which went through two printings in Athens. Afterwards, in 1952, the book, The Meaning of Icons, written jointly by Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, was published in Switzerland in both a German and an English edition. Its English text has been twice re-published in the United States.

Then a proposal was made for a serious theological study by Leonid Ouspensky of Orthodox Church art for inclusion in the encyclopedic German work, The Symbolism of Religions, which amounted to the dedication of half the volume to Orthodoxy. In 1954, the Moscow Patriarchate initiated theological pastoral courses in Paris, and included a course on the theology of icons, entrusted again to Ouspensky. This course laid the foundation for his monumental Theology of the Icon, volume one of which was published by the Exarchate in Paris in French in 1960. An English translation of this was published in New York in 1978. When Ouspensky continued work on volume two, he heavily revised and removed certain parts of the original volume one. The new and complete Theologie de l’Icone appeared in French in 1980. It was subsequently re-translated into English by another translator, and appeared in the United States in 1992; its Russian version appeared posthumously in 1989.

In the following years Leonid Ouspensky contributed articles on icons to the Journal of the Exarchate, which became chapters in a book published in Paris in 1980. An English translation of this work was edited for publication in New York in 1992. At the same time he published articles in response to questions about the iconostasis, the iconography of Pentecost, and so forth.

Leonid Ouspensky had a great capacity for work. His usual workday consisted of thirteen to fourteen hours, during which he would pass from icon painting to carving to restoration, sometimes a little metal repousse, leaving the evenings and Feastdays for writing articles and books. He wrote with difficulty, slowly, and with great effort. He said, before his death, that he had not yet managed to say what was, in his view, the most important thing.

In 1945, Leonid Ouspensky and his wife applied for the restitution of their Soviet citizenship and received it in June, 1946. Their first visit to Russia since their exile in the 1920’s came in 1958, at which time they began visiting Russia quite frequently. Each of these trips was rich and unforgettable in its own way, providing opportunities for continuing first-hand research and the study of old icons.

Leonid Ouspensky did not like public appearances. He accepted an invitation of the Church of Finland only twice to deliver lectures, and in 1969, on the invitation of the Sorbonne, he gave a course of lectures there. But he remembered with special warmth and joy the five lectures he gave in 1969 at the Theological Academy in Saint Petersburg — then Leningrad. He was pleased with the audience’s evident love and interest and with their many questions. The Russian Church awarded Leonid Ouspensky the Order of Saint Vladimir of the second — and later of the first — degree.

Leonid Ouspensky died in the night of the 11th-12th of December, 1987. During the illness preceding his death he confessed and received Holy Communion several times — the last time, five days before the end, when he could no longer confess, but was still conscious. He is buried in the Russian cemetery at Sainte Genevieve des Bois.

This biography is taken from the book, Recovering the Icon: The Life and Work of Leonid Ouspensky, by Father Patrick.